Stacks

2021-05-28 | Shiplet

Hi! So, every once in a while, even pros need to get back to the basics. And seeing as how I've been in the industry since 2014 and my only formal education was a 12-week part-time bootcamp at the beginning of 2015, getting back to the basics for me is, in many ways, an initial exploration of the basics. I'm sure I'm not the only person in this position, so I'm gonna try out the tried and true method of learning by teaching.

Today, I'm going over:

Stacks

Stacks are a data structure. What's a data structure? A data structure is a way of organizing data and logic which optimizes for certain use cases and/or real-world scenarios that need to read and write to memory efficiently & predictably.

So stacks are data structures, but what exactly does that mean, and how does it fit into the world as we know it?

Undo/Redo

A perfect example of using a stack in daily life is when you hit Ctrl-z or Cmd-z to undo the last operation you performed.

Take for example the act of typing each letter of your name into an input box while signing up for an account on a website.

Each key you press generates an event that's stored by the browser, and the browser stores those events in - you guessed it - a stack!

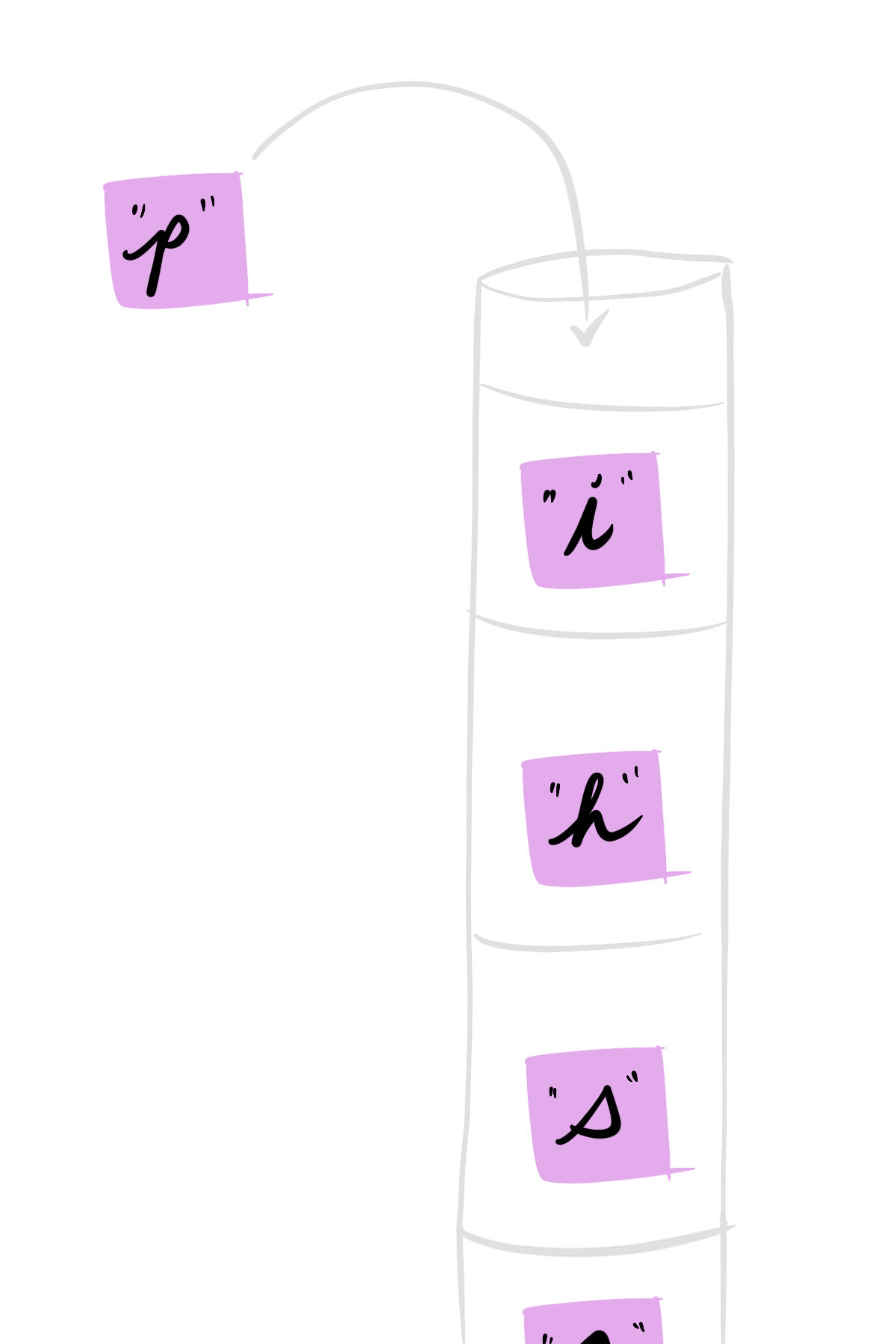

Each letter-in-a-box above represents one of those events, and they're entered into the stack in the order they occur.

When you hit your "undo" shortcut, the browser goes to the stack of events, removes the top, most recent event, and reverses the operation it performed.

This act of taking the top, most recent item off of the stack is known as a pop. Conversely, adding an item to the end of a stack is known as a push.

Why Stacks?

So why use a stack here instead of, say, an array?

A lot of it comes down to the understanding that stacks only work in this way.

You don't index into a stack the way you do an array.

You don't modify stacks at arbitrary locations like you might an array or an object/hashmap.

You've really only got 2 or 3 operations you can perform with a stack: pop, push, which we've already covered, and peek, which is like pop, but it doesn't alter the contents of the stack; it just returns the value of the topmost item.

They also frequently have helper methods that let you know the length of the stack, and whether or not it's empty.

In short, stacks are great at being a repository of high-performance, low-maintenance breadcrumbs: a way for your algorithm or program to retrace its steps to a prior state in memory.

That's why they're used for undo operations, but they're commonly used in compilers while reading syntax tokens, as well as pathfinding algorithms in order to track decisions.

You'll also encounter one of the most common use cases while debugging an application: the call stack.

Each item of a call stack represents a function call and the program context under which it was called.

This allows each layer the program, procedure, or subroutine to quickly resume the proper memory context once the function below it returns or finishes.

How am I Supposed to Know These Things Unless I'm Taught Them?

This is a question I ask myself every time I encounter a new concept in Computer Science. "How does everybody just know these things? Is it obvious to everyone but me?" You'll be glad to know that no! it's not obvious to everybody but you! Stacks didn't actually, formally exist as a concept until 1955, when their initial specification was published in a German Computer Science journal, and the first patent for a stack wasn't filed until 1957. Of course, Alan Turing hinted at their existence as far back as 1946, but it still took 9 years after that for them to show up as a standard.

I take comfort in things like this because it means that someone at some point in history spent a lot of time trying to solve a very particular set of problems, and this thing, which in programming today seems so common, was what they came up with. It just so happens that it was a good idea and stuck around!

Okay, So How Do I Build One?

In my experience, programming languages don't typically include a default implementation of stacks in their prelude or standard library.

The justifications I've seen given for why is that stacks, while useful, aren't actually used in most day-to-day programming problems.

And, if a stack is needed, it's usually a straightforward process to modify the language's support for arrays or vectors to create one.

So let's do that!

Let's build a stack in JavaScript and then for fun compare it to one built in Rust.

This comparison will also highlight a very important distiction with stacks - their values should always be of the same type.

Remember, the basic building blocks of a stack are 3, sometimes 4 methods, and 1 property:

push: (method) adds an item to the end of the stackpop: (method) returns and removes the last item of the stackpeek: (method) returns the last item of the stack without removing itisEmpty: (method) returns a boolean indicating if the stack is emptylength: (property) returns the length of the stack

Given those parameters, here's the simplest definition of a JavaScript stack I can think of.

Notice how it's wrapping JS's standard implementation of an array.

The array forms the backbone of the stack, but as long as you're using the Stack class, the only values you're concerned about are the topmost value, the length of the stack, and whether it's empty.

There's no splice, or slice, or accessing stackItem[5] - there's only the methods and property defined below.

class Stack {

constructor() {

this.stack = []; // The standard JS array ✌

}

get length() {

return this.stack.length;

}

// pushes the value onto the end of the stack

// mutates the stack

push(value) {

this.stack.push(value);

}

// removes the topmost item from the stack

// mutates the stack

pop() {

return this.stack.pop();

}

// returns the value of the topmost item

// but does not mutate the stack

peek() {

return this.stack[this.length - 1];

}

isEmpty() {

return this.length === 0;

}

}Not too shabby huh? If you Google "javascript stack", this is probably line-for line an exact copy of what you'll find out on the web. Of course, there are some additional guardrails you can add and questions you can ask, such as:

- What happens if you call

popon an empty stack? - How big should you allow the stack to get?

- How would you go about writing a

flushfunction that empties the entire stack?

Now let's take a look at one written in Rust.

It has a lot of similarities to JavaScript, but some key differences as well.

The first being that Rust doesn't really have a concept of a Class the same way more recent versions of JavaScript do.

Rust has Structs and Enums, which can have object-like characteristics, but are their own entities.

For a more in-depth discussion of these differences, see my post Core Rust Features for Non-Rustaceans.

The other thing to notice here is that, because Rust is statically typed, and in order to make our Stack usable for a wider range of data types, it contains some generic parameters.

Generic parameters signal to the Rust compiler that you anticipate this struct being used for a wide variety of data types.

I'll call these out in code comments below.

However, generics also enforce, at the compiler level, the rule I stated before we dove into the JS solution: a stack's values should all be of the same type. You can get similar functionality with TypeScript, but because it ultimately transpiles down to JavaScript, I wanted to include an example where the language/compiler will refuse to build if there's any chance of violating the type safety (unless you explicitly account for it).

// src/main.rs

// the `<T>` here is the generic.

// it creates a marker that we use in later method definitions

// to indicate that every operation should expect the same

// type of data

struct Stack<T> {

stack: Vec<T>

}

impl<T> Stack<T> {

// this creates a new Stack instance.

// you might notice the vec![] doesn't have a specific type annotation.

// this is because Rust is smart enough to infer the type after the first

// time you use it.

pub fn new() -> Stack<T> {

Stack {

stack: vec![]

}

}

// because `push` mutates the stack, we have to explicitly borrow `self`

// as mutable

pub fn push(&mut self, value: T) {

&self.stack.push(value);

}

// returning a type of Option<T> signals we should

// be prepared to handle cases where there's no data left

pub fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<T> {

self.stack.pop()

}

pub fn peek(&self) -> Option<&T> {

self.stack.get(self.stack.len() - 1)

}

pub fn len(&self) -> usize {

self.stack.len()

}

pub fn is_empty(&self) -> bool {

self.stack.len() == 0

}

}Some clarifications: the impl block is Rust's way of saying, "implement these methods for this data type."

So in the case of our Stack struct, we have a stack property, which is of a type Vec<T> or a "vector of data of type T, whatever T might be."

That T could refer to integers, strings, or other more complex data types.

Notice also the difference between the return types of pop and peek.

pop returns an Option<T>, but peek returns Option<&T>.

The & in Option<&T> indicates we're returning a reference to the data at that location, rather than the data itself.

Whereas in pop, because it's Option<T>, we know that we're receiving the data itself, and that the data will no longer belong to the stack.

This is how Rust handles non-destructive vector indexing in this case, and I dig how explicit it is!

Stacks!

I hope this answers some questions about stacks! I definitely learned some new things and am feeling a bit more confident after writing it, so I can only hope that some of that transfers to you as well.

Up next are Queues! Stay tuned :)